Why Are Tech Reporters Sleeping On The Biggest App Store Story?

Browsers are the most likely disruptor of the mobile duopoly but you'd never know it reading Wired or The Verge.

The tech news is chockablock[1] with antitrust rumblings and slow-motion happenings. Eagle-eyed press coverage, regulatory reports, and legal discovery have comprehensively documented the shady dealings of Apple and Google's app stores. Pressure for change has built to an unsustainable level. Something's gotta give.

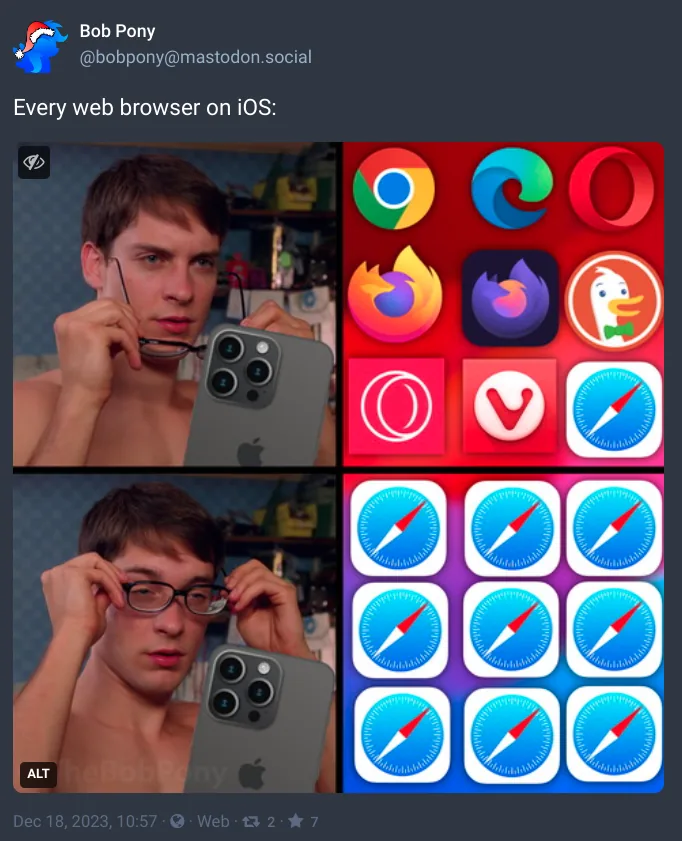

This is the backdrop to the biggest app store story nobody is writing about: on pain of steep fines, gatekeepers are opening up to competing browsers. This, in turn, will enable competitors to replace app stores with directories of Progressive Web Apps. Capable browsers that expose web app installation and powerful features to developers can kickstart app portability, breaking open the mobile duopoly.

But you'd never know it reading Wired or The Verge.

With shockingly few exceptions, coverage of app store regulation assumes the answer to crummy, extractive native app stores is other native app stores. This unexamined framing shapes hundreds of pieces covering regulatory events, including by web-friendly authors. The tech press almost universally fails to mention the web as a substitute for native apps and fail to inform readers of its potential to disrupt app stores.

"An app is just a web-page wrapped in enough IP to make it a crime to defend yourself against corporate predation."

The implication is clear: browsers unchained can do to mobile what the web did to desktop, where more than 70% of daily "jobs to be done" happen on the web.

Replacing mobile app stores will look different than the web's path to desktop centrality, but the enablers are waiting in the wings. It has gone largely unreported that Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) have been held back by Apple and Google denying competing browsers access to essential APIs.[2]

Thankfully, regulators haven't been waiting on the press to explain the situation. Recent interventions into mobile ecosystems include requirements to repair browser choice, and the analysis backing those regulations takes into account the web's role as a potential competitor (e.g., Japan's JFTC (pdf)).

Regulators seem to understand that:

- App stores protect proprietary ecosystems through preferential discovery and capabilities.

- Stores then extract rents from developers dependent on commodity capabilities duopolists provide only through proprietary APIs.

- App portability threatens the proprietary agenda of app stores.

- The web can interrupt this model by bringing portability to apps and over-the-top discovery through search. This has yet to happen because...

- The duopolists, in different ways, have kneecapped competing browsers along with their own, keeping the web from contesting the role of app stores.

Apple and Google saw what the web did to desktop, and they've laid roadblocks to the competitive forces that would let history repeat on smartphones.

The Buried Lede #

The web's potential to disrupt mobile is evident to regulators, advocates, and developers. So why does the tech news fail to explain the situation?

Consider just one of the many antitrust events of recent months. It was covered by The Verge, Mac Rumors, Apple Insider, and more.

None of the linked articles note browser competition's potential to upend app stores. Browsers unshackled have the potential to free businesses from build-it-twice proprietary ecosystems, end rapacious app store taxes, pave the way for new OS entrants — all without the valid security concerns side-loading introduces.

Lest you think this an isolated incident, this article on the impact of the EU's DMA lacks any hint of the web's potential to unseat app stores. You can repeat this trick with any DMA story from the past year. Or spot-check coverage of the NTIA's February report.

Reporters are "covering" these stories in the lightest sense of the word. Barrels of virtual ink has been spilt documenting unfair app store terms, conditions, and competition. And yet.

Disruption Disrupted #

In an industry obsessed with "disruption," why is this David vs. Goliath story going untold? Some theories, in no particular order.

First, Mozilla isn't advocating for a web that can challenge native apps, and none of the other major browser vendors are telling the story either. Apple and Google have no interest in seeing their lucrative proprietary platforms supplanted, and Microsoft (your narrator's employer) famously lacks sustained mobile focus.

Next, it's hard to overlook that tech reporters live like wealthy people, iPhones and all. From that vantage point, it's often news that the web is significantly more capable on other OSes (never mind that they spend much of every day working in a desktop browser). It's hard to report on the potential of something you can't see for yourself.

Also, this might all be Greek. Reporters and editors aren't software engineers, so the potential of browser competition can remain understandably opaque. Stories that include mention of "alternative app stores" generally fail to mention that these stores may not be as safe, or that OS restrictions on features won't disappear just because of a different distribution mechanism, or that the security track records of the existing duopolist app stores are sketchy at best. Under these conditions, it's asking a lot to expect details-based discussion of alternatives, given the many technical wrinkles. Hopefully, someone can walk them through it.

Further, market contestability theory has only recently become a big part of the tech news beat. Regulators have been writing reports to convey their understanding of the market, and to shape effective legislation that will unchain the web, but smart folks unversed in both antitrust and browser minutiae might need help to pick up what regulators are putting down.

Lastly, it hasn't happened yet. Yes, Progressive Web Apps have been around for a few years, but they haven't had an impact on the iPhones that reporters and their circles almost universally carry. It's much easier to get folks to cover stories that directly affect them, and this is one that, so far, largely hasn't.

Green Shoots #

The seeds of web-based app store dislocation have already been sown, but the chicken-and-egg question at the heart of platform competition looms.

On the technology side, Apple has been enormously successful at denying essential capabilities to the web through a strategy of compelled monoculture combined with strategic foot-dragging.

As an example, the eight-year delay in implementing Push Notifications for the web[3] kept many businesses from giving the web a second thought. If they couldn't re-engage users at the same rates as native apps, the web might as well not exist on phones. This logic has played out on a loop over the last decade, category-by-category, with gatekeepers preventing competing browsers from bringing capabilities to web apps that would let them supplant app stores[2:1] while simultaneously keeping them from being discovered through existing stores.

Proper browser choice could upend this situation, finally allowing the web to provide "table stakes" features in a compelling way. For the first time, developers could bring the modern web's full power to wealthy mobile users, enabling the "write once, test everywhere" vision, and cut out the app store middleman — all without sacrificing essential app features or undermining security.

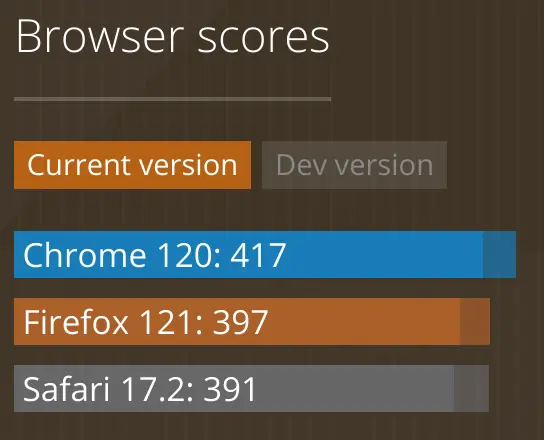

Sunsetting the 30% tax requires a compelling alternative, and Apple's simultaneous underfunding of Safari and compelled adoption of its underpowered engine have interlocked to keep the web out of the game. No wonder Apple is massively funding lobbyists, lawyers, and astroturf groups to keep engine diversity at bay while belatedly battening the hatches.

On the business side, managers think about "mobile" as a category. Rather than digging into the texture of iOS, Android, and the differing web features available on each, businesses tend to bulk accept or reject the app store model. One sub-segment of "mobile" growing the ability to route around highway robbery Ts & Cs is tantalising, but not enough to change the game; the web, like other metaplatforms, is only a disruptive force when pervasive and capable.[4]

A prohibition on store discovery for web apps has buttressed Apple's denial of essential features to browsers:

Google's answer to web apps in Play is a dog's breakfast, but it does at least exist for developers willing to put in the effort, or for teams savvy enough to reach for PWA Builder.

Recent developments also point to a competitive future for capable web apps.

First, browser engine choice should become a reality on iOS in the EU in 2024, thanks to the plain language of the DMA. Apple will, of course, attempt to delay the entry of competing browsers through as-yet-unknown strategies, but the clock is ticking. Once browsers can enable capable web apps with easier distribution, the logic of the app store loses a bit of its lustre.

Work is also underway to give competing browsers a chance to facilitate PWAs that can install other PWAs. Web App Stores would then become a real possibility through browsers that support them, and we should expect that regulatory and legislative interventions will facilitate this in the near future. Removed from the need to police security (browsers have that covered) and handle distribution (websites update themselves), PWA app stores like store.app can become honest-to-goodness app management surfaces that can safely facilitate discovery and sync.

It's no surprise that Apple and Google have kept private the APIs needed to make this better future possible. They built the necessary infrastructure for the web to disrupt native, then kept it to themselves. This potential has remained locked away within organisations politically hamstrung by native app store agendas. But all of that is about to change.

This begs the question: where's the coverage? This is the most exciting moment in more than 15 years for the web vs. native story, but the tech press is whiffing it.

A New Hope #

2024 will be packed to the gills with app store and browser news, from implementation of the DMA, to the UK's renewed push into mobile browsers and cloud gaming, to new legislation arriving in many jurisdictions, to the first attempts at shipping iOS ports of Blink and Gecko browsers. Each event is a chance to inform the public about the already-raging battle for the future of the phone.

It's still possible to reframe these events and provide better context. We need a fuller discussion about what it will mean for mobile OSes to have competing native app stores when the underlying OSes are foundationally insecure. There are also existing examples of ecosystems with this sort of choice (e.g., China), and more needs to be written about the implications for users and developers. Instead of nirvana, the insecure status quo of today's mobile OSes, combined with (even more) absentee app store purveyors, turns side-loading into an alternative form of lock-in, with a kicker of added insecurity for users. With such a foundation, the tech-buying public could understand why a browser's superior sandboxing, web search's better discovery, and frictionless links are better than dodgy curation side-deals and "beware of dog" sign security.

The more that folks understand the stakes, the more likely tech will genuinely change for the better. And isn't that what public interest journalism is for?

Thanks to Charlie, Stuart Langride, and Frances Berriman for feedback on drafts of this post.

Antitrust is now a significant tech beat, and recent events frequently include browser choice angles because regulators keep writing regulations that will enhance it. This beat is only getting more intense, giving the tech press ample column inches to explain the status quo more deeply and and educate around the most important issues.

In just the last two months:

-

Google lost to Epic in a jury trial that determined Google's Play Store is an illegal monopoly.

-

Google lost all assumption of good faith as evidence from the Epic trial showed the Play team to be scoundrels, two-timers, and cretins who were willing to set shockingly unfair terms for anyone with enough market power to embarrass them. And that's before we get to the light attempted bribery.

-

Google's witness also blurted out a statistic that is both anodyne and damning: 36%. That's what Google pays Apple in search rev-share for default search placement in Safari. Normally, this would be a detail of a boring business deal. In context, however, it highlights Apple's decade-long suppression of iOS browser competition — combined with poverty-level funding of WebKit — which has skimmed tens of billions in profit per year from the web while starving browser development. This has deprived users, businesses, and web developers of safe (but critical) capabilities. It wasn't just Play that buggered the mobile web; Google was happy to outsource the dirty deed too.

-

Apple lost on an appeal to keep the UK's Competition and Market Authority (CMA) investigation into browsers and cloud gaming on ice.[5]

-

In December, Apple declined to appeal to the UK's Supreme Court for reasons that remain opaque.

Perhaps Apple didn't appeal because, in November, the UK unexpectedly brought forward the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill. It looks set to become law early in the new year, standing up a regulator with real teeth who, one presumes, will not be predisposed to think well of Apple's delay of its predecessor's investigations.

-

Meanwhile, in the EU, Apple attempted to wriggle out of regulations that might bring about proper browser choice by arguing that Safari is actually three under-performing browsers. in a marketing trenchcoat[6].

-

On the other side of the planet, news just broke that Japan will bring forward legislation to target app store shenanigans. Given the JFTC's earlier findings about how interlocking layers of control have kept browsers from contesting app store prominence, we can expect some spicy legislative language around browsers.

-

Australia has also just agreed (in principle) to do the same, including language that acknowledges the role suppressing browser choice has had in preventing the web from competing with mobile native app ecosystems.

All but one of the 19 links above are from just the last 60 days, a period which includes a holiday break in the US and Europe. With the EU's DMA coming into force in March and the CMA back on the job, browser antitrust enforcement is only accelerating. It sure would be great if reporters could occasionally connect these dots. ↩︎

-

The stories of how Apple and Google have kept browsers from becoming real app stores differ greatly in their details, but the effects have been nearly identical: only their browsers could offer installation of web apps, and those browsers have done shockingly little to support web developers who want to depend on the browser as the platform.

The ways that Apple has undermined browser-based stores is relatively well known: no equivalent to PWA install or "Smart Banners" for the web, no way for sites to suppress promotion of native apps, no ability for competing browsers to trigger homescreen installation until just this year, etc. etc. The decade-long build of Apple's many and varied attacks on the web as a platform is a story that's both tired and under-told.

Google's malfeasance has gotten substantially less airtime, even among web developers – nevermind the tech press.

The story picks up in 2017, two years after the release of PWAs and Push Notifications in Chrome. At the time, the PWA install flow was something of a poorly practised parlour trick: installation used an unreliable homescreen shortcut API that failed on many devices with OEM-customised launchers. The shortcut API also came laden with baggage that prevented effective uninstall and cross-device sync.

To improve this situation, "WebAPKs" were developed. This new method of installation allows for deep integration with the OS, similar to the Application Identity Proxy feature that Windows lets browsers to provide for PWAs, with one notable exception: on Android, only Chrome gets to use the WebAPK system.

Without getting into the weeds, suffice to say many non-Chrome browsers requested access. Only Google could meaningfully provide this essential capability across the Android ecosystem. So important were WebAPKs that Samsung gave up begging and reverse engineered it for their browser on Samsung devices. This only worked on Samsung phones where Suwon's engineers could count on device services and system keys not available elsewhere. That hasn't helped other browsers, and it certainly isn't an answer to an ecosystem-level challenge.

Without WebAPK API access, competing browsers can't innovate on PWA install UI and can't meaningfully offer PWA app stores. Instead, the ecosystem has been left to limp along at the excruciating pace of Chrome's PWA UI development.

Sure, Chrome's PWA support has been a damn sight better than Safari's, but that's just damning with faith praise. Both Apple and Google have done their part to quietly engineer a decade of unchallenged native app dominance. Neither can be trusted as exclusive stewards of web competitiveness. Breaking the lock on the doors holding back real PWA installation competition will be a litmus test for the effectiveness of regulation now in-flight. ↩︎ ↩︎

Push Notifications were, without exaggeration, the single most requested mobile Safari feature in the eight years between Chromium browsers shipping and Apple's 2023 capitulation.

It's unedifying to recount all of the ways Apple prevented competing iOS browsers from implementing Push while publicly gaslighting developers who requested this business-critical feature. Over and over and over again. It's also unhelpful to fixate on the runarounds that Apple privately gave companies with enough clout to somehow find an Apple rep to harangue directly. So, let's call it water under the bridge. Apple shipped, so we're good, right?

Right?

I regret to inform you, dear reader, that it is not, in fact, "good".

Despite most of a decade to study up on the problem space, and nearly 15 years of of experience with Push, Apple's implementation is anything but complete.

The first few releases exposed APIs that hinted at important functionality that was broken or missing. Features as core as closing notifications, or updating text when new data comes in. The implementation of Push that Apple shipped could not allow a chat app to show only the latest message, or a summary. Instead, Apple's broken system leaves a stream of notifications in the tray for every message.

Many important features didn't work. Some still don't.. And the pathetic set of customisations provided for notifications are a sick, sad joke.

Web developers have once again been left to dig through the wreckage to understand just how badly Apple's cough "minimalist" cough implementation is compromised. And boy howdy, is it bad.

Apple's implementation might have passed surface-level tests (gotta drive up that score!), but it's unusable for serious products. It's possible to draw many possible conclusions from this terrible showing, but even the relative charity of Hanlon's Razor is damning.

Nothing about this would be worse than any other under-funded, trailing-edge browser over the past three decades (which is to say, a bloody huge problem), except for Apple's well-funded, aggressive, belligerent ongoing protest to every regulatory attempt to allow true browser choice for iPhone owners.

In the year 2024, you can have any iOS browser you like. You can even set them as default. They might even have APIs that look like they'll solve important product needs, but as long as they're forced to rely on Apple's shit-show implementation, the web can't ever be a competitive platform.

When Apple gets to define the web's potential, the winner will always be native, and through it, Apple's bottom line. ↩︎

The muting effect of Apple's abuse of monopoly over wealthy users to kneecap the web's capabilities is aided by the self-censorship of web developers. The values of the web are a mirror world to native, where developers are feted for adopting bleeding-edge APIs. On the web, features aren't "available" until 90+% of all users have access to them. Because iOS is at least 20% of the pie), web developers don't go near features Apple fails to support. Which is a lot.

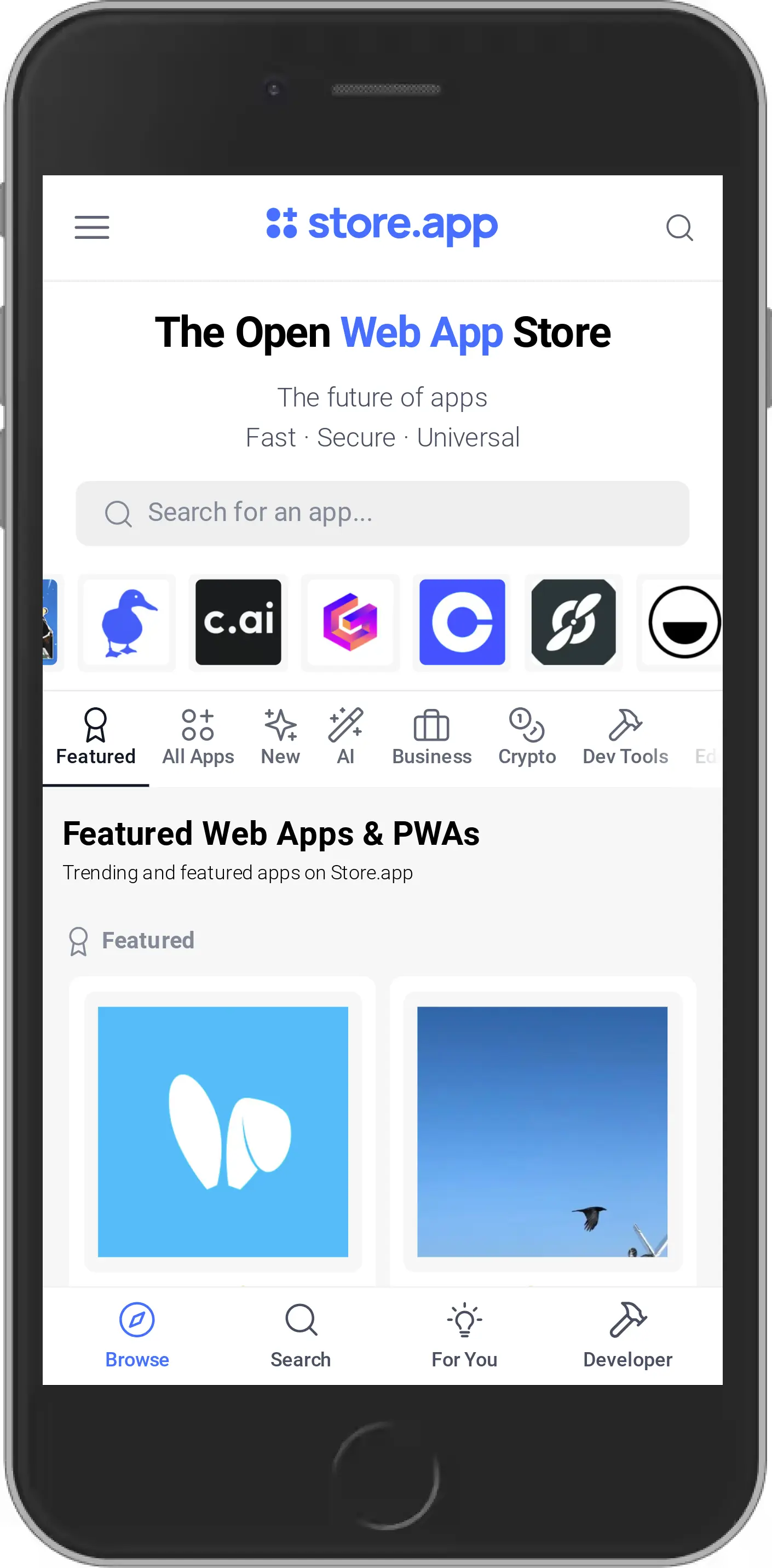

caniuse.com's "Browser Score" is one way to understand the scale of the gap in features that Apple has forced on all iOS browsers.

The Web Platform Tests dashboard highlights 'Browser Specific Failures', which only measure failures in tests for features the browser claims to support. Not only are iOS browsers held back by Apple's shockingly poor feature support, but the features that _are_ available are broken so often that many businesses feel no option but to retreat to native APIs that Apple doesn't break on a whim, forcing the logic of the app store on them if they want to reach valuable users. Apple's pocket veto over the web is no accident, and its abuse of that power is no bug.

Native app stores can only take an outsized cut if the web remains weak and developers stay dependent on proprietary APIs to access commodity capabilities. A prohibition on capable engines prevents feature parity, suppressing competition. A feature-poor, unreliable open web is essential to prevent the dam from breaking.

Why, then, have competing browser makers played along? Why aren't Google, Mozilla, Microsoft, and Opera on the ramparts, waving the flag of engine choice? Why do they silently lend their brands to Apple's campaign against the web? Why don't they rename their iOS browsers to "Chrome Lite" or "Firefox Lite" until genuine choice is possible? Why don't they ask users to write their representatives or sign petitions for effective browser choice? It's not like they shrink from it for other worthy causes.

I'm shocked by not surprised by the tardiness of browser bosses to seize the initiative. Instead of standing up to unfair terms, they've rolled over time and time again. It makes a perverse sort of sense.

More than 30 years have passed since we last saw effective tech regulation. The careers of those at the top have been forged under the unforgiving terms of late-stage, might-makes-right capitalism, rather than the logic of open markets and standards. Today's bosses didn't rise by sticking their necks above the parapets to argue virtue and principle. At best, they kept the open web dream alive by quietly nurturing the potential of open technology, hoping the situation would change.

Now it has, and yet they cower.

Organisations that value conflict aversion and "the web's lane is desktop" thinking get as much of it as they care to afford. ↩︎

Recall that Apple won an upset victory in March after litigating the meaning of the word "may" and arguing that the CMA wasn't wrong to find after multiple years of investigations that Apple were (to paraphrase) inveterate shitheels, but rather that the CMA waited too long (six months) to bring an action which might have had teeth.

Yes, you're reading that right; Apple's actual argument to the Competition Appeal Tribunal amounted to a mashup of rugged, free-market fundamentalist " but mah regulatory certainty!", performative fainting into strategically placed couches, and feigned ignorance about issues it knows it'll have to address in other jurisdictions.

Thankfully, the Court of Appeals was not to be taken for fools. Given the harsh (in British) language of the reversal, we can hope a chastened Competition Appeal Tribunal will roll over less readily in future. ↩︎

If you're getting the sense that legalistic hair-splitting is what Apple spends its billion-dollar-per-year legal budget on because it has neither the facts nor real benefits to society on its side, wait 'till you hear about some of the stuff it filed with Japan's Fair Trade Commission!

A clear strategy is being deployed. Apple:

- First claims there's no there there (pdf). When that fails...

- Claims competitors that it has expressly ham-strung are credible substitutes. When that fails...

- Claims security would suffer if reasonable competition were allowed. Rending of garments is performed while prophets of doom recycle the script that the sky will fall if competing browsers are allowed (which would, in turn, expand the web's capabilities). Many treatments of this script fill the inboxes of regulators worldwide. When those bodies investigate, e.g. the history of iOS's forced-web-monoculture insecurity, and inevitably reject these farcical arguments, Apple...

- Uses any and every procedural hurdle to prevent intervention in the market it has broken.

The modern administrative state indulges firms with "as much due process as money can buy", and Apple knows it, viciously contesting microscopic points. When bluster fails, huffingly implemented, legalistic, hair-splitting "fixes" are deployed on the slowest possible time scale. This strategy buys years of delay, and it's everywhere: browser and mail app defaults, payment alternatives, engine choice, and right-to-repair. Even charging cable standardisation took years longer than it should have thanks to stall tactics. This maximalist, joined-up legal and lobbying strategy works to exhaust regulators and bamboozle legislators. Delay favours the monopolist.

A firm that can transform the economy of an entire nation just by paying a bit of the tax it owes won't even notice a line item for lawyers to argue the most outlandish things at every opportunity. Apple (correctly) calculates that regulators are gun-shy about punishing them for delay tactics, so engagement with process is a is a win by default. Compelling $1600/hr white-shoe associates to make ludicrous, unsupportable claims is a de facto win when delay brings in billions. Regulators are too politically cowed and legally ham-strung to do more, and Apple plays process like a fiddle. ↩︎